- What Is The Indifference Curve In Economics?

- Key Concepts Of Indifference Curve Analysis

- What Are The Properties Of Indifference Curve?

- Formula Of Indifference Curve

- Understanding The Analysis Process Of IC

- Indifference Curve Map

- Indifference Curve Schedule

- Marginal Rate Of Substitution (MRS)

- Utility In Indifference Curve

- Uses & Benefits Of Indifference Curve

- Criticisms & Challenges of the Indifference Curve

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Indifference Curve: Definition, Properties, Formula, And Benefits

Indifference curves are used extensively in welfare economics to study consumer behaviour. They help economists understand how changes in prices or income affect consumers' consumption patterns.

Through indifference schedules and maps, economists can map out different indifference curves for different commodities and analyze the trade-offs consumers face when making decisions.

What Is The Indifference Curve In Economics?

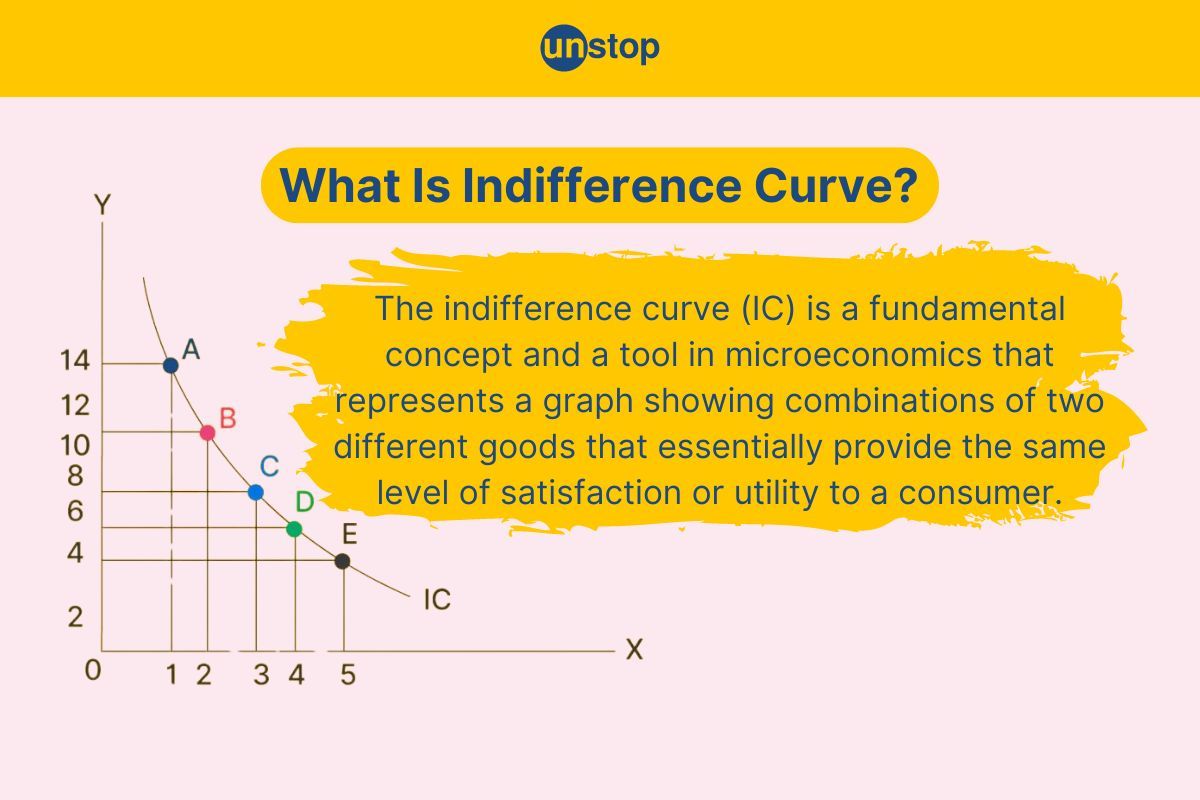

The indifference curve (IC) is a fundamental concept and important tool in microeconomics that represents a graph showing combinations of two different goods that essentially provide the same level of satisfaction or utility to a consumer.

Each point on an indifference curve (graph) indicates a combination of goods that the consumer considers equally preferable.

Key Concepts Of Indifference Curve Analysis

Let us study some of the important concepts involved in indifference curve analysis:

Indifference Curves

These curves represent all the possible combinations of two different goods that provide the same level of satisfaction to the consumer. Each curve represents a different level of utility, with higher curves indicating higher utility levels.

Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS)

This is the rate at which a consumer is willing to give up one good in exchange for another while maintaining the same level of utility. It is the slope of the indifference curve at any given point. The MRS typically decreases as one moves down the curve, reflecting diminishing marginal utility.

Utility

This is a measure of satisfaction or happiness that a consumer receives from consuming goods and services. Utility is subjective and varies from person to person.

Budget Constraints

Budget constraints show all the combinations of two different goods that a consumer can buy based on their income and the prices of those goods. On a graph, this line is straight, with one good plotted along the x-axis and the other along the y-axis. The slope of this line depends on how much each good costs compared to one another.

Budget Line

In the context of indifference curve analysis, a budget line represents all the combinations of two different goods that a consumer can afford to purchase given their income and the prices of the goods. It is a crucial component used to determine the consumer's optimal choice of goods, as it shows the trade-offs a consumer faces between the two goods within their budget constraint.

Consumer Equilibrium

Consumer Equilibrium happens when an indifference curve touches the budget line. This is the moment when a consumer gets the most satisfaction possible within their spending limits. At this point, the slope of the indifference curve, known as the MRS, matches the slope of the budget line, which represents the price ratio. This shows that the consumer is making the best use of their money between the two products.

What Are The Properties Of Indifference Curve?

The indifference Curve has several important properties that help in understanding consumer preferences and behaviour. Here are the main properties of indifference curves:

Convexity

Indifference curves are generally convex to the origin. This convexity represents the diminishing marginal rate of substitution (MRS). As a consumer substitutes one good for another, the additional satisfaction (marginal utility) gained from consuming more of one good decreases, requiring more of the other good to maintain the same utility level.

Downward Sloping

Indifference curves generally slope downwards from the left to the right. This means that when you have more of one good, you need to have less of the other good to keep your satisfaction level the same. This shows how the two goods are related in terms of what you give up for one to gain the other.

Non-Intersecting

Indifference curves cannot intersect. Each indifference curve represents a different level of utility, so if two curves were to intersect, it would imply that the same combination of goods provides two different levels of satisfaction, which is impossible.

Higher Curves Represent Higher Utility

Indifference curves further from the origin represent higher levels of utility. This means that any bundle of goods on a higher indifference curve provides greater satisfaction than any bundle on a lower indifference curve, assuming both curves are based on the same two goods.

Continuous & Smooth

Indifference curves are usually assumed to be continuous and smooth, reflecting the assumption that consumer preferences are consistent and that there are no sudden jumps in utility. This smoothness also implies that consumers can make infinitely small adjustments in consumption.

Non-Satiation

Indifference curve analysis often assumes the non-satiation principle, which means that more of a good is always preferred to less. This assumption ensures that indifference curves slope downwards and do not bend backwards.

MRS Decreases Along The Curve

The Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS)—the rate at which a consumer is willing to trade one good for another while maintaining the same level of utility—decreases as one moves down along the indifference curve. This is because as the consumer has more of one good, they are willing to give up less of the other good to obtain additional units of the first good.

Points Inside Indifference Curves

The area enclosed by an indifference curve represents all possible combinations of goods that provide an equal level of satisfaction or utility. However, not all points within this area are equally desirable for a consumer.

Points inside an indifference curve represent combinations with lower levels of satisfaction compared to those on the curve itself. Consumers always aim for bundles on higher indifference curves to maximize their utility.

Formula Of Indifference Curve

Indifference curves do not have a specific formula that applies universally, as they represent different levels of utility for different consumers and sets of goods. However, if we assume a utility function U(x,y) that represents a consumer's preferences for two goods, x and y, an indifference curve can be represented by setting the utility function equal to a constant level of utility, say U0.

This gives us the general form: U(x,y)=U0

Example Of Utility Function

For illustration, consider a common type of utility function: the Cobb-Douglas utility function. It is often used in economics due to its properties and simplicity.

U(x,y)=xayb

Here, x and y are quantities of two goods, and a and b are positive constants representing the consumer's preference intensities for the respective goods.

Understanding The Analysis Process Of IC

Having studied the key concepts of indifference curve, let us now look at how the analysis process is carried out in IC:

Plotting Indifference Curves & Budget Constraint: The first step involves plotting the indifference curves and the budget line on the same graph. The budget line is drawn based on the consumer's income and the prices of the two goods.

Finding the Tangency Point: The point where the highest possible indifference curve touches (is tangent to) the budget line indicates the optimal combination of goods that the consumer can afford. This point of tangency represents the consumer's equilibrium, where the MRS equals the price ratio of the two goods.

Determining Optimal Consumption Bundle: The coordinates of the tangency point indicate the quantities of the two goods that the consumer will choose to purchase to maximize their utility.

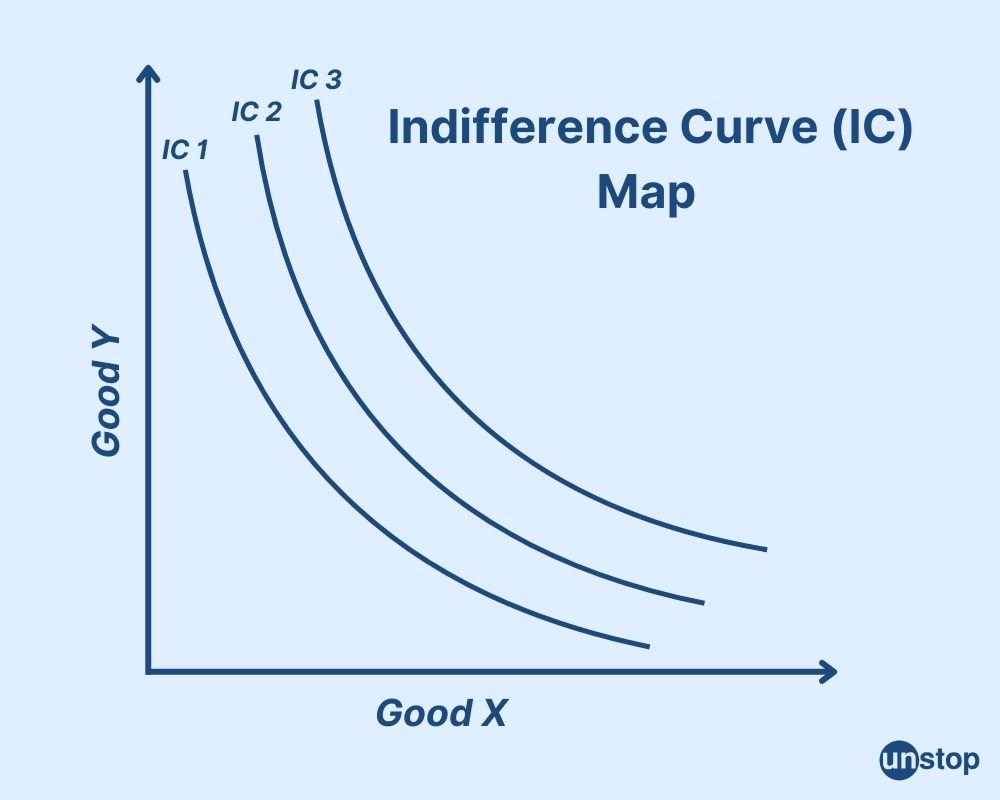

Indifference Curve Map

An indifference curve map is a graphical representation that shows a set of indifference curves for a consumer, illustrating their preferences across various combinations of two goods. This map helps in understanding how a consumer values different combinations of goods and how these values change across different levels of satisfaction.

Example Indifference Map

Imagine a consumer's preferences for two goods, x and y, are represented by the following indifference curves:

-

Curve 1: Represents a utility level of 10.

-

Curve 2: Represents a utility level of 20.

-

Curve 3: Represents a utility level of 30.

Each curve would show combinations of x and y that provide the same level of satisfaction. Curve 3 would be further from the origin than Curve 2, which in turn would be further from the origin than Curve 1, illustrating that higher curves correspond to higher levels of utility.

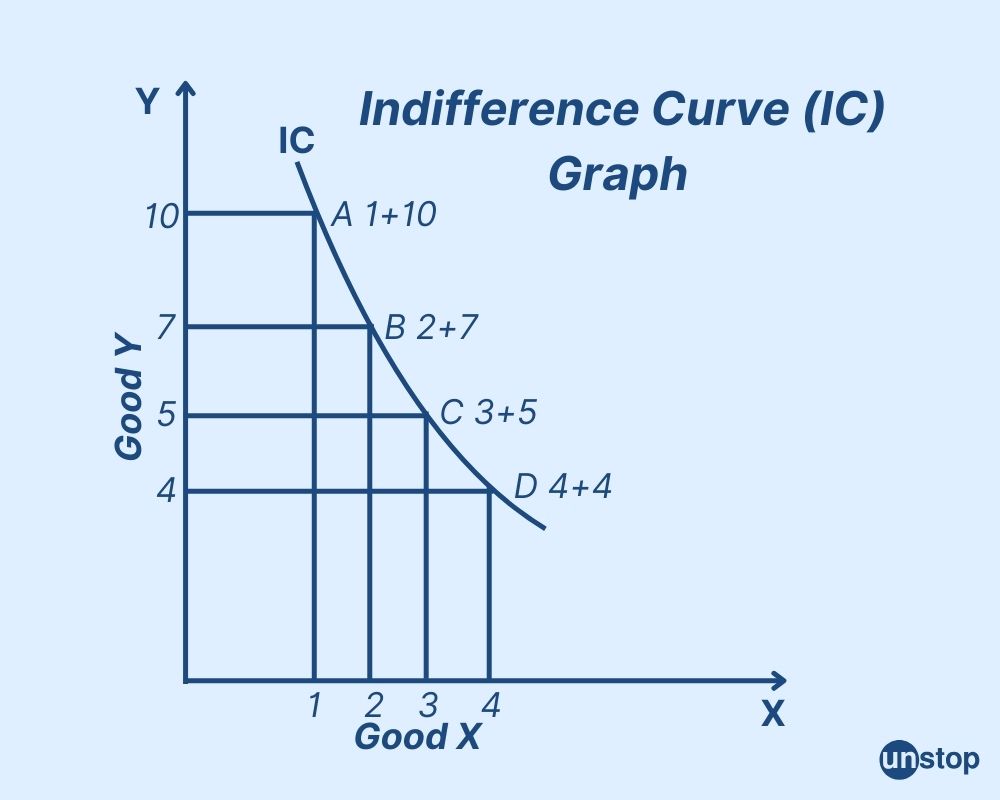

Indifference Curve Schedule

An indifference curve schedule is a table that displays various combinations of two products that give a consumer the same amount of satisfaction or utility. It shows different sets of goods along with their utility levels, helping to explain the consumer's choices and the trade-offs they make between these items.

Example Indifference Curve Schedule

Suppose we are analyzing a consumer's preferences for two goods, x and y. The indifference curve schedule might look something like this:

| Bundle | Quantity of Good x | Quantity of Good y | Utility Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2 | 8 | 100 |

| B | 4 | 6 | 100 |

| C | 6 | 4 | 100 |

| D | 8 | 2 | 100 |

In this schedule:

-

All bundles (A, B, C, and D) provide the same utility level of 100.

-

Each combination of x and y listed (A, B, C, and D) lies on the same indifference curve, representing a constant level of satisfaction.

Marginal Rate Of Substitution (MRS)

The Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS), in the context of an indifference curve, represents the rate at which a consumer is willing to trade one good for another while maintaining the same level of utility or satisfaction. It is essentially the slope of the indifference curve at any given point.

The MRS is typically negative because as a consumer acquires more of one good, they usually give up some amount of the other good, reflecting a trade-off. As a consumer moves along an indifference curve, consuming more of one good and less of another, the MRS generally diminishes.

This means that the consumer is willing to give up less of the second good for each additional unit of the first good, illustrating the principle of diminishing marginal utility.

The absolute value of MRS indicates the consumer's willingness to substitute between the two goods. A higher MRS suggests a greater willingness to substitute one good for the other, while a lower MRS indicates a lower willingness.

Example Of MRS

If a consumer is willing to give up 2 units of good y for 1 additional unit of good x without changing their overall satisfaction, the MRS would be 2. This means the consumer values an additional unit of x as much as they value 2 fewer units of y.

Utility In Indifference Curve

Utility in the context of indifference curve analysis refers to the satisfaction or pleasure a consumer derives from consuming goods and services. It is a measure of the consumer's preference for different combinations of goods, often expressed as a numerical value.

Quantification of Satisfaction

Utility is a numerical representation of the level of satisfaction a consumer gets from consuming a particular bundle of goods. While utility itself is abstract and not directly measurable, it provides a useful way to compare different consumption bundles.

Utility Function

The utility function U(x,y) represents the relationship between the quantities of goods consumed and the utility derived from them. For example, U(x,y) might denote the utility a consumer receives from consuming quantities x and y of two goods.

Constant Utility

Along a given indifference curve, the utility remains constant. This means that the consumer is indifferent between the various combinations of goods represented on the curve because they all yield the same level of satisfaction.

Ordinal Nature

In indifference curve analysis, utility is typically considered ordinal rather than cardinal. This means that the exact numerical value of utility is not important; rather, the ranking of preferences is key. It only matters that one bundle is preferred over another, not by how much.

Higher Utility Levels

Indifference curves further from the origin represent higher levels of utility. This means that a bundle on a higher indifference curve is preferred to a bundle on a lower indifference curve, as it provides greater satisfaction.

Example

If a consumer has a utility function U(x,y)=xy, this function defines the level of utility derived from consuming x units of good x and y units of good y. An indifference curve for a utility level of 10 would consist of all combinations of x and y such that xy=10.

Uses & Benefits Of Indifference Curve

The indifference curve offers several benefits in understanding and analyzing consumer behaviour. Here are some key benefits and usages:

Understanding Consumer Preferences

Indifference curves help visualize and understand how consumers make choices between different combinations of goods. They illustrate preferences and trade-offs, showing how consumers value different goods relative to one another.

Illustrating Trade-offs

Indifference curves show the trade-offs a consumer is willing to make between two goods. This helps in understanding how changes in the availability or price of one good might affect the consumption of another, providing insights into consumer decision-making.

Deriving the Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS)

By analyzing the slope of the indifference curve, one can determine the Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS), which indicates how much of one good a consumer is willing to give up to obtain one more unit of another good while maintaining the same level of utility. This concept is crucial for understanding consumer choices and preferences.

Analyzing Consumer Equilibrium

The indifference curve is used in conjunction with budget constraints to determine the consumer's equilibrium—where the highest indifference curve is tangent to the budget line. This equilibrium point shows the optimal combination of goods that maximizes a consumer's utility given their budget constraints.

Predicting Changes In Consumption

Indifference curve analysis helps predict how changes in prices or income affect consumption patterns. By observing shifts or rotations in the budget line and their interaction with the indifference curves, one can predict how consumers will adjust their consumption.

Illustrating Substitution & Income Effects

When analyzing the effects of price changes on consumption, indifference curves help separate the substitution effect (how consumption changes due to changes in relative prices) from the income effect (how consumption changes due to changes in real income).

Designing Economic Policies

Understanding consumer preferences and behaviour through an indifference curve can aid in designing and evaluating economic policies, such as taxation, subsidies, and welfare programs. It helps policymakers predict how changes in policies will affect consumer welfare and behavior.

Consumer Surplus Calculation

Indifference curves, in conjunction with demand curves, can be used to calculate consumer surplus, which measures the difference between what consumers are willing to pay and what they actually pay for goods and services.

Analysis Of Substitutes

Indifference curves can also reveal whether goods are substitutes or complements. If two goods are substitutes, an increase in the quantity consumed of one good leads to a decrease in the quantity consumed of the other.

In contrast, if two goods are complements, an increase in the quantity consumed of one good leads to an increase in the quantity consumed of the other.

Criticisms & Challenges of Indifference Curve

While indifference curves are a foundational concept in consumer theory, they do face several criticisms and challenges. Here are some of the main issues:

Assumption of Rational Preferences

Indifference curves assume consumers have consistent and rational preferences. In reality, consumer behaviour can be influenced by irrational choices and cognitive biases, which may not fit the model.

Difficulty in Measuring Utility

Utility, the core concept in indifference curves, is abstract and cannot be directly measured. This limits the analysis to ordinal comparisons rather than precise measurements of satisfaction.

Non-Convex Preferences

Indifference curves are typically assumed to be convex, reflecting diminishing marginal rates of substitution. However, some preferences may be non-convex (e.g., perfect complements), which do not fit the standard model.

Complex Preferences

The simple representation of preferences with indifference curves may not capture the complexity of real-world preferences involving many goods or intricate consumption patterns.

Conclusion

Indifference curves offer a powerful and intuitive framework for understanding consumer preferences and decision-making. By graphically representing the trade-offs between different goods, they illuminate how consumers allocate their resources to maximize satisfaction. The analysis of these curves reveals key insights into the marginal rate of substitution, consumer equilibrium, and the effects of price and income changes.

Ultimately, indifference curves not only enhance our grasp of economic behaviour but also provide critical tools for policymakers and businesses to predict and influence consumer choices. Their ability to simplify complex preferences into clear, visual insights makes them indispensable in both theoretical and practical economics.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How does the indifference curve represent consumer preferences?

Indifference curves depict different combinations of goods or services that provide consumers with equal satisfaction or utility. They illustrate how consumers make choices based on their preferences for certain combinations of goods over others.

2. Can two indifference curves intersect?

No, two indifference curves cannot intersect. If they were to intersect, it would violate the assumption that higher levels of consumption are preferred to lower levels.

3. What is the relationship between the marginal rate of substitution (MRS) and convexity?

The MRS measures the rate at which a consumer is willing to give up one good for another while maintaining constant satisfaction. The convexity of an indifference curve reflects how the MRS changes as more units of one good are substituted for another.

4. How do income changes affect an indifference curve?

Changes in income can shift an individual's budget constraint and consequently impact their consumption possibilities. This can lead to shifts in indifference curves as preferences change due to alterations in purchasing power.

5. Are all goods suitable for analysis using indifference curve theory?

Indifference curve analysis assumes that goods are divisible and continuous, meaning they can be measured along a continuum rather than being discrete or binary choices.

Suggested reads:

Instinctively, I fall for nature, music, humor, reading, writing, listening, traveling, observing, learning, unlearning, friendship, exercise, etc., all these from the cradle to the grave- that's ME! It's my irrefutable belief in the uniqueness of all. I'll vehemently defend your right to be your best while I expect the same from you!

Login to continue reading

And access exclusive content, personalized recommendations, and career-boosting opportunities.

Subscribe

to our newsletter

Comments

Add comment